Complexity, Experience, and Decision-Making

Introduction

I have been meaning to write this post for a while as it follows nicely from my most recent one on decision-making. It also dives into the experience of complexity, which is incredibly important. In this post, I want to single out decision-making in complex situations. Parts of the following will be similar to an earlier post titled "How Complex Situations Feel." The post goes in a new direction by braiding together decision-making, explanation, and the experience of complexity.

It's Complex!

How do we experience situations that we call complex? Edgar Morin (2002) writes “When someone says, ‘It’s complex.... the word complex does not constitute an explanation, but rather indicates the difficulty of explaining. The word serves to designate something we really can't explain" (p.325). Explanations are something we experience and are said to ourselves, to others, and by others to us.

Explaining

But what is in an explanation? Where is the difficulty located when we try to explain something complex? According to Maturana (1988), explanations have two components. The first component is the formal condition. The formal condition is generated out of our or someone else’s experience. Formal conditions are proposed as the source behind the event being explained. They are a proposition for what caused our experience.

The second component is the informal condition. Informal conditions belong to the person who is accepting the explanation. This is the case even if they are explaining to themselves. The informal condition shapes the formal condition by deciding if it is acceptable (Maturana & Verden-Zöller, 2008). If the formal condition is rejected based on the generally tacit criteria of the informal condition, a new formal condition is created. The cycle continues until a passable formal condition is proposed.

Experience

Explaining is an experience. It involves language and the embodied process of devising a mechanism capable of producing an observed effect. The same holds true for explaining complex situations-it is an experience. As with any explanation, there is first the lived experience of observing an event, then deciding if the observed event is in need of explanation. As already discussed, there is then the act of drawing from one's experience to put forth a formal condition. Perhaps unique to complexity is the presence of ambiguity, paradox, and uncertainty. The prior may evoke feelings such as awe, strangeness, or confusion.

Returning to Morin (2002), where in Maturana’s process is the difficulty of explaining complexity found? Is it in generating a formal condition that would sufficiently explain the complex situation? Or is the difficulty in successfully passing through one or more informal conditions?

Causality

Perhaps both of the above situations are true. The outcome in both cases is a failure to establish causal relationships. An inability to suggest a formal condition and have it be accepted by an informal condition is about cause and effect. The cause is the formal condition that is proposed as being responsible for the effect observed. Whether the causal relationship is accepted and becomes inculcated into practice depends on the informal condition. Difficulty at either stage disrupts the forming of the cause-and-effect relationship and cascades into decision-making.

Complexity

The above indicates that it is difficult to explain complex situations. The ramifications of this are considerable. The act of explaining a situation precedes any decision-making. Before it can be decided what to do, the complex situation must be made sense of. This "making sense" is partly facilitated by explaining the still unfolding events. Explained events inform decisions: "This and this is happening because of such and such so we should do this and that."

What if, as Morin ( 2002) suggests, when faced with complexity there is an ever-present difficulty in explaining? Meaning, what if the question of what cause is involved in producing what effect can never quite be established? The prior causes a gap in knowledge about how a complex situation works. This of course makes decision-making harder as nothing has been firmly established. There is nothing for one to "hang their hat on" in the decision-making process -- nothing to go off of with complete certainty.

Based on the author's experience, decision-makers may use causal relationships previously experienced as shortcuts in new settings (I believe Klein mentions this as well). While there is merit to this approach, even subtle misalignment between old and current causal relationships can be problematic. If it is held that causes are producing certain effects based on past experience when they are not in the current context, operations may devolve. The prior is the role of experience. There may also exist a tendency to bring new experiences of complex situations into existing domains of knowledge (Maturana, 1995). In doing so, events become inculcated into established bodies of experience. This can close the decision-maker to the novelty of the complex situation where they miss important patterns, cues, and uniqueness.

So, now What?

We are frequently confronted with complex situations in which we observe phenomena we really cannot explain. As a result, we are left with awe and strangeness (Maturana, 1988; Maturana, 1995). Furthermore, the inability to explain what has been observed causes problems for decision-makers, as they lack any stable relationships of cause and effect to proceed from.

The situation described above leaves decision-makers with ambiguity, wonder, uncertainty, and a feeling of oddness. If this is the situation and it is indeed unavoidable, how does one move forward? One first step that might be taken is to visualize a decision being made about a complex situation that can support decision-making.

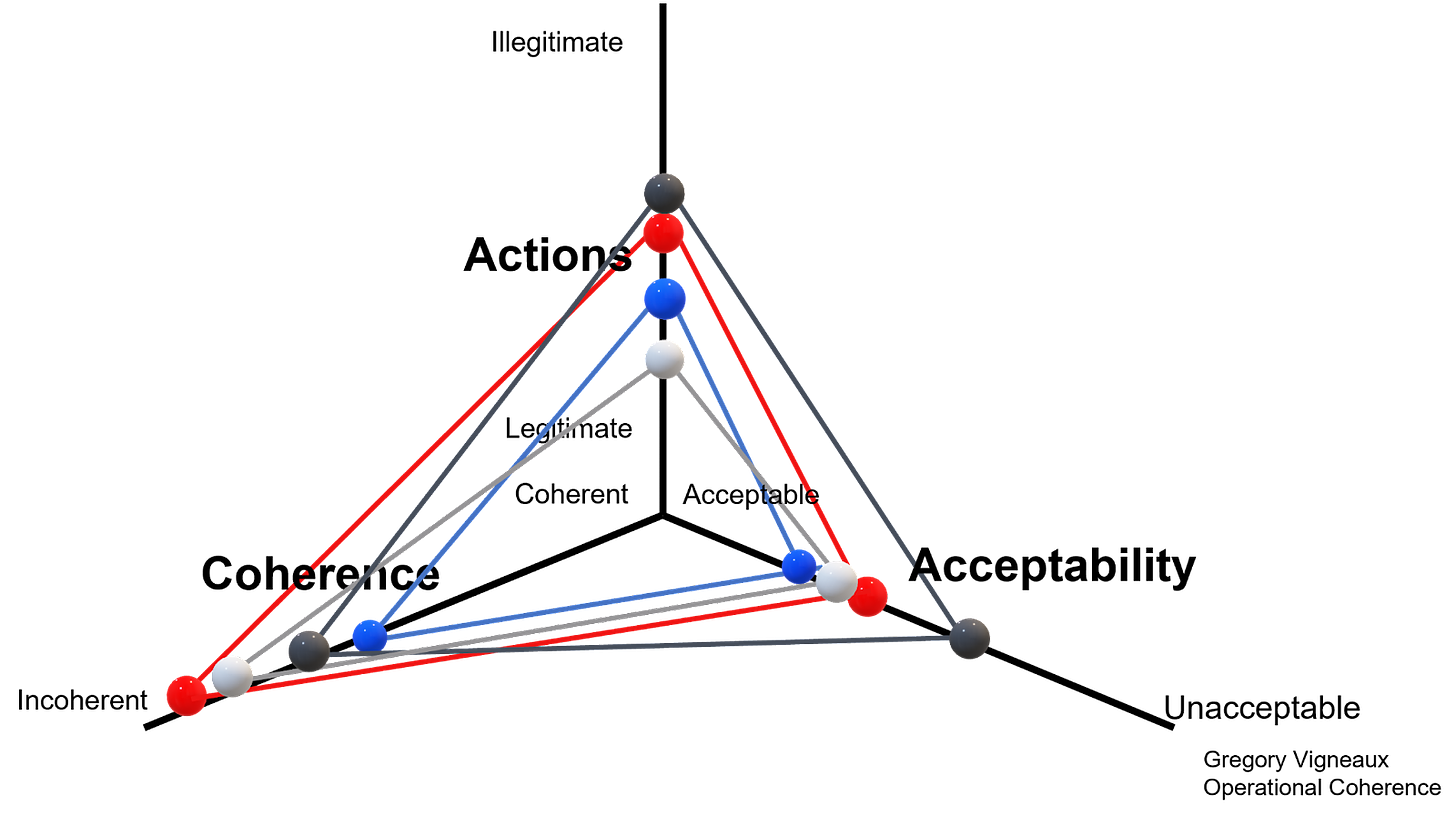

The above shows the mapping of multiple decision-maker's evaluations of a decision made about a complex situation. First, the coherence (as it is defined in the earlier post) of the decision is low – it does not correspond with the decision group's collective map of the world. Much of this lack of coherence stems from not being able to explain the situation. There simply is not a coherent picture to base decisions on. There may be glimpses of emphermeral coherence or shadows of it here and there, but a stable coherent image does not exist. It is unknown how the situation and its multiple observed events are functioning, interrelating, and are interdependent of one another. However, even in the presence of this ambiguity and peculiarity, it does not mean that the actions the decision will unfold into cannot be seen as legitimate and that the decision can be evaluated as acceptable even though coherence is low. Courses of action can still appear as legitimate and decisions can still be accepted by the group. Acceptability and legitimacy can somewhat decouple from coherence while it remains an important variable. Coherence being rated as poor may be part of the experience of dealing with complex situations. Moving forward with a decision evaluated as having minimal coherence signals decision-makers to pay close attention to shifts in the environment that merit new decisions. There is is a need to stay nimble as the information that can be gained from the situation changes.

Conclusion

It has been established that it is difficult to explain complex situations and that explanations involve two components involved with the forming and accepting of causal relationships. Furthermore, explanations and their linking of cause and effect are foundational to decision-making. Decision-makers should not expel excessive amounts of energy to resolve the difficulty of explaining (as it is probable they will never do so). Instead, they should embrace the ambiguity, uncertainty, strangeness, and awe, that accompanies the difficulty of explaining and absorb it as part of the experience of making decisions in complex environments. A lack of coherence can exist at the same time as courses of action are found legitimate and decisions are evaluated as acceptable.

In closing, for decision-makers, explaining experiences of complex situations in new ways may lead to new ways of acting (Maturana & Verden-Zöller, 2008). That is, it leads to not integrating experiences into existing bodies of knowledge but establishing new ones. New domains of knowledge derived from experience can be established by looking toward the situation instead of back at previous ones.

References

Maturana, H. R. (1995). The nature of time. Chilean School of Biology of Cognition.

Maturana, H. R. (1988). Reality: The search for objectivity or the quest for a compelling argument. The Irish Journal of Psychology,, 9(1), 25-82. doi:10.1080/03033910.1988.10557705

Maturana, H. R., & Verden-Zöller, G. (2008). The origin of humanness in the biology of love. (B. Pille, Ed.) Exeter, Devon, UK: Imprint Academic.

Morin, E. (2002). The epistemology of complexity. In J. Schnitman, & D. F. Schnitman (Eds.), New paradigms, culture and subjectivity (pp. 325-341). Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.