The Cluster Approach: Another Incident Response System

Disclaimer: I wrote this paper 5 years ago.

Introduction

In 2005, inspired by issues with recent humanitarian responses, the United Nations commissioned an independent assessment of the global humanitarian response system. The information produced by this assessment, the Humanitarian Response Review (HRR), was used to guide and support reform of the humanitarian system. The central intent of this reform was to strengthen and improve the effectiveness of humanitarian response across the globe in part by increasing predictability and accountability, and strengthening relationships between government, non-government (NGO), and international organizations (Streets, et al., 2010; Inter-Agency Standing Committee, 2006). A component of this reform was the introduction of the cluster approach as a system of coordinating humanitarian responses. In alignment with the overall intent of the reform, the adoption and introduction of the cluster approach by the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) in 2005 was intended to strengthen humanitarian responses through increasing capacity, providing predictable leadership, building partnerships, increasing accountability, and closing other gaps identified by the HRR (Inter-Agency Standing Committee, 2006). Since the introduction of the cluster approach, it has continuously evolved in response to unique conditions posed by incidents and the needs of humanitarian actors (Streets, et al., 2010). Throughout this period, considerable strengths and shortcomings of this approach have been identified, though it has been asserted the true potential of the cluster approach has yet to be realized (Binder & Grunewald, 2010).

Overview

The cluster approach is a coordination system and not a command and control system like the Incident Command System (Coppola, 2005; United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, 2014). Without mechanisms of command and control, the cluster approach promotes and depends on close coordination, cooperation, planning, and collaboration, built on a foundation of respect for differences among the involved humanitarian actors and unrestricted by traditional bureaucratic organization (Coppola, 2005; Inter-Agency Standing Committee, 2006; United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, 2014). If this occurs, effective lateralization within and between clusters will lead to the emergence of meta-organization fitting for the complexity of humanitarian emergencies (Burkle, Jr. & Hayden, 2011; Okros, Verdun, & Chouinard, 2011). In the context of humanitarian response, advantages of a coordination system over a command and control oriented system include involvement from stakeholders “…whose actions are not necessarily dictated by...command and control systems” (Coppola, p.370, 2015) such as NGO’s and local actors. This allows for the building of local capacity, engaging from the bottom-up, adaptation of structure to the unique conditions posed by an incident, and increased autonomy of the involved actors (Burkle, Jr. & Hayden, 2011; Coppola, 2005). The theoretical basis of this approach, cluster theory, was popularized by Porter in 1998 who describes clusters as “…geographic concentrations of interconnected companies…in a particular field (Porter, p.78, 1998). Porter describes the form of organization clusters represent as a middle ground between market and bureaucracy, fitting for the emergence of the global market, that offers flexibility unencumbered by vertical organization or the maintenance of formal partnerships (Cumming-Bruce, 2009; Jahre & Jensen, 2015; Porter, 1998).

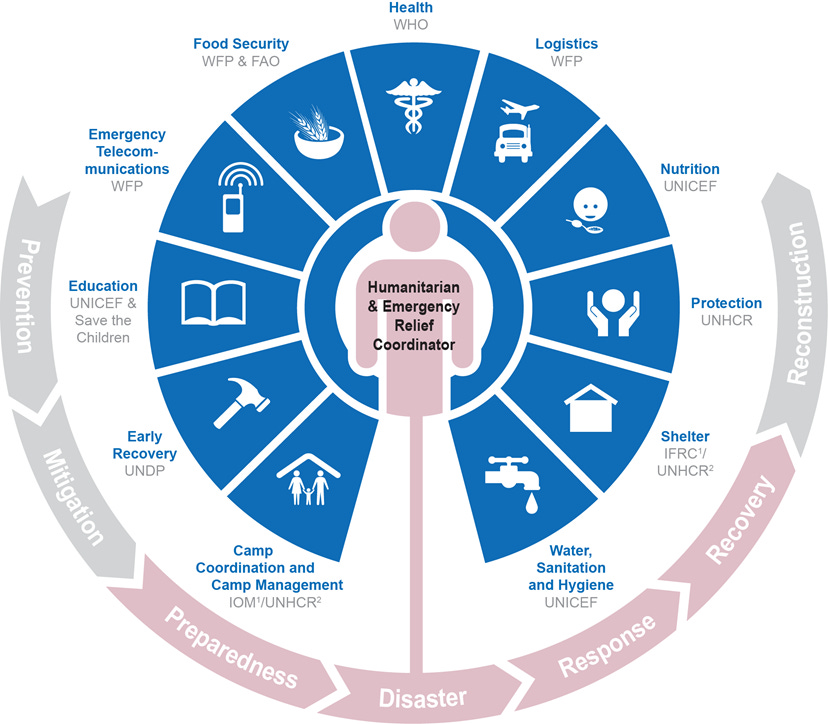

The overall purpose of the cluster approach is to provide a system of coordination that ensures “…international responses to humanitarian emergencies are predictable and accountable and have clear leadership by making clearer the division of labor between organizations, and their roles and responsibilities in different areas” (Inter-Agency Standing Committee, p.3, 2015). This is accomplished in part by organizing humanitarian actors by functional area of response into 11 different clusters such as health, nutrition, and logistics (See Table 1). Though each cluster is concerned with a different functional area of response, there are several cross-cutting issues, such as gender, race, and the environment, which span across all clusters (Inter-Agency Standing Committee, 2006).

Coordination and Support

Within the cluster approach there are two distinct levels – global and country. At the global level the lead agencies of each cluster provide a global cluster coordinator, identify best practice and develop standards and policy, increase response capacity through training and stockpiling supplies, and provide operational support to country level clusters (Jahre & Jensen, 2015; Stumpenhorst, Stumpenhorst, & Razum, 2011). Global cluster leads are accountable directly to the Emergency Relief Coordinator (ERC) in the United Nation’s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) (Coppola, 2005; Inter-Agency Standing Committee, 2006). If an unfolding disaster requires a humanitarian response, or it appears that one is imminent, the ERC may designate a Humanitarian Coordinator (HC) who will assign cluster lead agencies at the country level based upon local capacity. Once established, country level clusters are accountable to the HC and should align their actions with the policies, standards, and norms established by global clusters – though there is no formal line of accountability between global and country leads (Inter-Agency Standing Committee, 2006). Country level lead agencies are responsible for ensuring “… well-coordinated and effective humanitarian responses” (Inter-Agency Standing Committee, p.7, 2006), though the lead agencies are not solely responsible for accomplishing this. Cluster lead agencies are not accountable for all of the humanitarian actors in their cluster, nor are the actors accountable to the lead agency (Inter-Agency Standing Committee, 2006). Cluster lead agencies are also “Providers of Last Resort,” meaning that if gaps in response exist beyond cross-cutting issues and their central functional area of response, they are to act in a way that reduces these gaps. The application of the cluster approach does not necessarily mean that the HC will be running the incident, country or sub-country level governments may remain in command throughout the response (Inter-Agency Standing Committee, 2006).

Transformation

While analyzing the cluster approach it is important to consider the deviation a results-focused coordination system is from a traditional performance and process-centric bureaucratic command and control system. As such, it necessitates a significant process of organizational change (Coppola, 2005; Inter-Agency Standing Committee, 2015; Sanger, 2008). This process is inherently complex, has been met with resistance, and will require significant cultural change that will support effective bottom-up collaboration and coordination that will lead to the realization of the cluster approach’s full potential (Binder & Grunewald, 2010). The cluster approach has evolved over time in response to the needs of the humanitarian actors and the incident. This is evident in the variations of the cluster approach’s application in response to various constraints such as security issues and external pressures (Streets, et al., 2010).

Strengths and Weaknesses

Since the 2005 adoption and its first application later that year in Pakistan, both strengths and shortcomings of the approach have been identified (Coppola, 2005; Stumpenhorst, Stumpenhorst, & Razum, 2011). Key among the strengths found thus far, are the promotion of a learning organization, evident in the above evolution of the approach, and in the actions of clusters focusing attention on issues affecting the response, increasing peer accountability, improved leadership, and strengthened partnerships between humanitarian actors (Streets, et al., 2010). The 2013 IASC Transformative Agenda found that the application of the cluster approach had been “overly-process driven” (IASC, p.5, 2015) which may have detracted from the cluster approach’s overall functionality by not allowing it to function as a true coordination system dependent on operational level coordination and cooperation (Inter-Agency Standing Committee, 2015). Shortcomings have been identified in areas including coordination, accountability, unnecessary centralization, poor communication and coordination, competition between NGOs, and timely cluster lead agency meetings (Streets, et al., 2010).

While issues have been found, an assessment of the cluster approach in six different countries offers that “…the benefits generated by the cluster approach to date already slightly outweigh its costs and shortcomings” (Streets, et al., p.9, 2010). This is visible in the creation of “the necessary conditions to improve the quality of humanitarian response (Binder & Grunewald, p.38, 2010). Improvements have been suggested, such as feedback mechanisms between NGOs and clusters regarding their actions, increased global support, greater inclusion of local and national humanitarian actors, and increased coordination and cooperation between clusters (Binder & Grunewald, 2010; Stumpenhorst, Stumpenhorst, & Razum, 2011; Streets, et al., 2010). Provided that improvements are made and the transformation process continues driven by support from humanitarian actors, the cluster approach has “…significant potential for further improving humanitarian response and thereby enhancing the well-being of affected populations” (Streets, et al., p.75, 2010). While continuing to strengthen humanitarian responses is the primary future implication of the cluster approach, continued success may serve as a model for the field of emergency management – demonstrating the importance of coordination. The experiences of country and global lead agencies and humanitarian actors may offer valuable insight regarding the organizational change process and successful collaboration, coordination, and cooperation, that could be used in the adoption of coordination systems around the world.

References

Binder, A., & Grunewald, F. (2010). IASC cluster approach evalutation, 2nd phase country study: Haiti. Global Public Policy Institute .

Burkle, Jr., F. M., & Hayden, R. (2011). The concept of assisted management of large-scale disasters by horizontal organizations. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine, 16(3), 87-96.

Coppola, D. P. (2005). Introduction to international disaster management (Third ed.). Waltham, MA: Elsevier Inc.

Cumbers, A., & McKinnon, D. (Eds.). (2013). Clusters in urban and regional developing. Routledge.

Cumming-Bruce, N. (2009). WHO takes lead on Health as UN tackles crises. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 250-251. doi:0.2471/BLT.09.020409

Humanitarian Response. (N.D.). What is the cluster approach? . Retrieved from https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/coordination/clusters/what-cluster-approach

Inter-Agency Standing Committee. (2006, November 24). Guidance note on using the cluster approach to strengthen humanitarian response. Retrieved from http://www.refworld.org/pdfid/460a8ccc2.pdf

Inter-Agency Standing Committee. (2015, November). Reference module for cluster coordination at the country level. Retrieved from https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/system/files/documents/files/iasc-coordination-reference%20module-en_0.pdf

Jahre, M., & Jensen, L.-M. (2015). Coordination in humanitarian logistics through clusters. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management,, 40(8/9), 657-674. doi:10.1108/09600031011079319

Klumpp, M., de Leeuw, S., Regattieri, A., & de Souza, R. (Eds.). (2015). Humanitarian logistics and sustainability. London: Spinger International Publishing .

Okros, A., Verdun, J., & Chouinard, P. (2011). The meta-organization: A researc and conceptual landscape. Defence R&D Canada - CSS. Retrieved from https://bbcsulb.desire2learn.com/d2l/le/content/312705/viewContent/2895788/View

Porter, M. E. (1998). Clusters and the new economics of competition. Harvard Business Review, 76(77), 77-90.

Sanger, B. M. (2008). Getting to the roots of change: Performance management and organizational culture. Public Performance & Management Review, 31(4), 621-653. doi:10.2753/PMR1530-9576310406

Streets, J., Grunewald, F., Binder, A., de Geoffroy, V., Kauffmann, D., Kruger, S., . . . Sokpoh, B. (2010). IASC cluster approach evaluation 2 synthesis report . Global Public Policy Institute.

Stumpenhorst, R., Stumpenhorst, M., & Razum, O. (2011). The UN OCHA cluster approach: gaps between theory. Journal of Public Health, 19(6), 587-592. doi:10.1007/s10389-011-0417-3

United Nations. (1991, 12 19). General Assembly: A/RES/46/182. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/documents/ga/res/46/a46r182.htm

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Human Affairs. (N.D.). Cluster Coordination . Retrieved from http://www.unocha.org/what-we-do/coordination-tools/cluster-coordination

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. (2014). Humanitarian civil-military coordination: A guide for the military. Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. Retrieved from https://docs.unocha.org/sites/dms/Documents/UN%20OCHA%20Guide%20for%20the%20Military%20v%201.0.pdf